It wasn't until I took an interest in genealogy that I wondered where the name Hollingsworth had come from. It turns out it was the name of the gentleman one of his great-aunts married. Apparently, my grandmother, who might just have had a few airs and graces about her, thought it was a rather distinguished name and so gave it to Billy, but Mr Hollingsworth was not related to him.

A tale of my grandfather

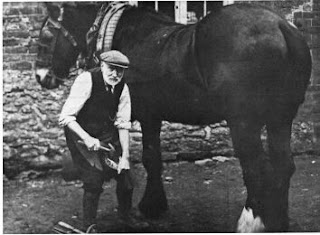

My grandfather had always been old, or so it seemed to me, a child of three or four, in those closing years of the First War. His hair I remember as a white foam that engulfed all of his face save his eyes, nose and cheekbones, and flowed on to his chest. (In the accompanying photograph he appears to have undergone a "tidying-up".) To my eyes at any rate, and in my memory, he markedly resembled those Old Testament prophets and patriarchs who, according to the illustrator of the massive family bible which was his favourite reading, were also white-bearded beings of dignified bearing.

He spoke in measured tones like the tall clock that stood in the corner of his living room. And it was my impression that he was supremely wise and knowledgeable. For had he not once been a scholar, taking with him the majestic sum of one penny for his learning whenever be attended school?

His home was in the then unspoilt village of Burton-on-Stather, in the north of the county. Take a few steps from his front door and you could look down upon the Trent - "smug and silver" in Shakespeare's opinion - and, beyond, the green levels of Yorkshire stretching away to misty distances.

In the centre of grandfather's world was his house, his home; and close round about, like bastions to a stronghold, stood his forge, his farm and - most important of all - his chapel.

The forge adjoined the house, and a scattering of discarded horse-shoes, broken ploughshares and various superannuated farm implements reached almost to grandfather's back door, as though stranded there by some rusty tide. To that same back door came a miscellany of requests, orders and pleas, ranging from repairs to giant traction engines to new handles on frying-pans. From any room in Grandfather's house your ear could catch the ring of hammer on anvil, or the shuddering snort of the forge bellows; or from time to time voices raised in exasperation (though not with oaths, if grandfather were present) and hooves thudding and scraping on flagstones as some restive horse, not taking kindly to new shoes, was led round and round in a tight circle to sweat the ginger out of him.

The pungent fume, "unforgettable, unforgotten", of charred hoof, the commotion, the hammer's song - these called me irresistibly. Grandfather would place a box for me to stand on so that the bellows handle, polished with use smooth as silk, and with a cow's horn on the end of it, came within my infant grasp. Many hours I spent pumping there and watching grandfather and his apprentices toiling over the white-hot iron; their shirt sleeves, I remember, being rolled up with the bunched cloth inside, next to the skin, so as not to catch and hold sparks.

All days brimmed with interest in the forge; but the high days were those when the wheelwright came with new waggon wheels to be fitted with their iron rims. In a corner of the yard set aside for this rite a great ring of fire was built to bring the huge iron hoop to white heat. Nearby, on a circular bed of iron plate, the parts of the wheel-to-be were assembled: in the centre the hub, always of wych-elm; then the spokes, set in the hub sockets and radiating to fit into other sockets in the six curved ash fellies that made up the rim of the wheel.

The men - and at these times extra help was enlisted - positioned themselves at the white-hot hoop, and on grandfather's command seized it in great tongs, lifted and fitted it round the circle of the fellies, and sledge-hammered it home. Then flames licked along the new wood and eyes and nose stung with the acrid smoke, presently mingled with steam clouds as water was sluiced over the hissing metal. Contracting, the hoop tightened and took fellies, spokes and hub in its iron grip. And a new wheel was born.

The managing of a small farm in harness with a blacksmith's shop was common enough in those days, but seems to be a way of life that has largely passed. Now more often than not we have the travelling blacksmith - if we have a blacksmith at all - complete with van, portable forge and oxy-acetylene welding gear.

Grandfathers farm, like his forge, entered his house via the back door. Bead-eyed fowls foraged as far as the kitchen. Baskets of eggs arrived, garnered from all manner of cunning or careless nooks and crannies around the farmyard; and apples rosy-cheeked from the orchard; and hams for salting and hanging. Commonly there was a litter on the scullery floor of chaff and straw stalks of bright gold; and of mud, or worse, shed from their boots when they came in for meals or family prayers by the two or three farmhands. One of these, I just remember, wore the old-fashioned farmworker's smock.

Grandfather was happier in his farm, I think, than in his forge: in his common tasks about the farm, and no task was too humble - he often sang to himself; in the forge only the hammer sang.

The North Wind doth blow,

And we shall have snow,

And what will the robin do then, poor thing?

He'll sit in the barn,

And keep himself warm,

And hide his head under his wing, poor thing.

Hymn tunes, too, usually of the brothers Wesley, were frequently on his lips, their strong rhythm chiming happily with the blows of the chopper when turnips were being "topped and tailed"; or with the spurting "whoosh-whoosh" of milk into the pail when grandfather sat on his three-legged stool, his half-turned head nuzzling into the cow's flank. Occasionally, very occasionally, he would twist the teat so that the white stream jetted into my face; but his customary mien of patriarch and prophet would remain unchanged, the only evidence of that impish moment being the warm dribble on my cheeks and chin.

Grandfather was old, as I have said, and somewhat deliberate in his ways, but he could move swiftly if there was need. In the barn stood a machine for crushing cattle-cake, which in those days reached the farm in the shape of large rectangles of corrugated sheet like thick green cardboard. There was a day when the cogs of this machine removed the end of one of my inquisitive fingers. This grandfather retrieved and wrapped in a handkerchief; then harnessed the pony to the trap and drove smartly into Winterton where Dr Baker, our nearest doctor, stuck the end in place again and bandaged it tightly. And there, without benefit of penicillin or sulphanamides, it grew and has remained fast, albeit slightly askew, to this day.

The farm had its high days no less than the forge. Days, for instance, when the reaper reduced the standing corn to a thin island rustling with rabbits, and the guns stood watchful. Days when I jolted home proudly on top of the last sheaves-laden waggon, or perched perilously on the broad back of Jessie or Lightning, the inside of my thighs sticky with the great shire's sweat. Or days when the mighty traction engine crunched into the stackyard, and the great leather driving-belt whirred and slapped, the bright grain bulged the sacks, chaff and dust choked eyes and nose, and rats bolted squeaking; and grandfather in charge of it all, conferring, directing, ordering, with one eye on the weather and one on the work.

The back door of grandfather's house, then, had mainly to do with the business of forge and farm. His front door was more concerned with chapel matters, and on Sundays it saw a good deal of traffic. Through it we sallied - aunts, uncles, cousins and any strangers within the gate - to early service and to all other services throughout the day. We marched off with grandfather, bible-black, in the van, in a group redolent of boot polish, mothballs and heavy serge suiting - an aroma which is what I take the dog Quoodle in Chesterton's poem to have had in mind when it referred to "the smell of Sunday morning". With grandfather in the front, that is to say unless he happened to be doing battle with Appolyon in some pulpit or meeting-house elsewhere; grandfather was a local preacher for 75 years. Thealby, Coleby, West Halton, Whitton, Wintringham, and places farther afield - it is staggering to reflect on the number of miles he must have covered, by push bike or pony and trap, in all weathers.

The back door of grandfather's house, then, had mainly to do with the business of forge and farm. His front door was more concerned with chapel matters, and on Sundays it saw a good deal of traffic. Through it we sallied - aunts, uncles, cousins and any strangers within the gate - to early service and to all other services throughout the day. We marched off with grandfather, bible-black, in the van, in a group redolent of boot polish, mothballs and heavy serge suiting - an aroma which is what I take the dog Quoodle in Chesterton's poem to have had in mind when it referred to "the smell of Sunday morning". With grandfather in the front, that is to say unless he happened to be doing battle with Appolyon in some pulpit or meeting-house elsewhere; grandfather was a local preacher for 75 years. Thealby, Coleby, West Halton, Whitton, Wintringham, and places farther afield - it is staggering to reflect on the number of miles he must have covered, by push bike or pony and trap, in all weathers."Our" chapel I remember most vividly as bare, unlovely indeed, and heavily impregnated with varnish. The colour-washed wall behind the pulpit proclaimed uncompromisingly, not to say stridently, in huge red, blue and green gothic lettering WE PREACH CHRIST CRUCIFIED. In those days, however, I confess to having been less interested in that piece of information than in the sideways drift of the tap-dancing vase of flowers on top of the throbbing harmonium; but the vase was invariably prodded back to safety in time, at the cost of a false note or two.

I do not know how long the tradition of family prayers was maintained in grandfather's house. Perhaps it was swept away, like so much else, by the First War. We met, all of us, including the farmhands, in an upper room. One of the grown-ups would read the lesson chosen by grandfather, and grandfather would deliver a prayer - or sometimes a reproof, as at a certain meeting for family prayers that followed immediately on Plough Monday, or "Plough Jag" day, as it was known with us. This was the first Monday after January 6th, the Old Christmas Day, and was the date by which the ploughing should be finished. By way of celebration the farmworkers decked themselves in ribbons and other finery, rode hobby horses and beat drums - and went the round of the village for beer money. Grandfather had come across one of his farmhands in the gutter; hence the reproof, the lightning-flash and the thunder-roll.

Normally, however, the meetings were simple, and short, and no doubt comforting enough for those old enough to appreciate them - unless, as sometimes happened, grandfather made a mistake in the numbering of chapter or verse, and the unfortunate reader found himself fairly launched on a terrifying ocean of "begats" and "begots" with every prospect of coming to grief on the rock of some crackjaw biblical surname. But you may be sure that any titter was hurriedly stifled when grandfather's Old Testament eyebrows knitted themselves in a stern bar across the top of his spectacles.

My abiding memory of my grandfather, though, is not one of sternness. I see him rather as often I saw him in an evening, his head bent to the Bible open on the table before him under the yellow light of the oil-lamp, a moth or two bumping against the glass chimney. His lips move in silence; his face is serene. One would like to think that for him, as for that other Pilgrim, when his time came "all the trumpets sounded on the other side".

That was almost 60 years ago. Grandfather's house has since been "modernised"; the forge is metamorphosed into a bungalow; the chapel is no more; the farm land is packed shoulder to shoulder with "desirable residences".

What remains? This?

W. H. Wood